The distribution of earthquakes (yellow dots in the NASA picture below) and volcanoes (red dots) on the Earth’s surface marks the boundaries (blue lines) of tectonic plates. Plates can be oceanic or continental lithosphere, as well as both. Volcanism and seismicity are the expression of plate interactions at their margins. Ocean rifts, where seafloors spread, are divergent boundaries, along which plates separate. Mountain belts also occur along plate margins.

A simplified map of tectonic plates from geology.about.com. You can count 15 plates, although today we know more than 50

The eminent English geologist Arthur Holmes (1890 – 1965), considered the father of modern geology, was the first to provide a plausible mechanism for lithospheric plate motion. Holmes, who started studying physics and later moved to geology, was the first to propose a geological time scale based on recent discoveries about radioactivity. His first evaluation of the age of the Earth was 4 billion years, the first to get significantly close to modern assessments. At 23 he was already an authority of geology.

Arthur Holmes (1890 – 1965)

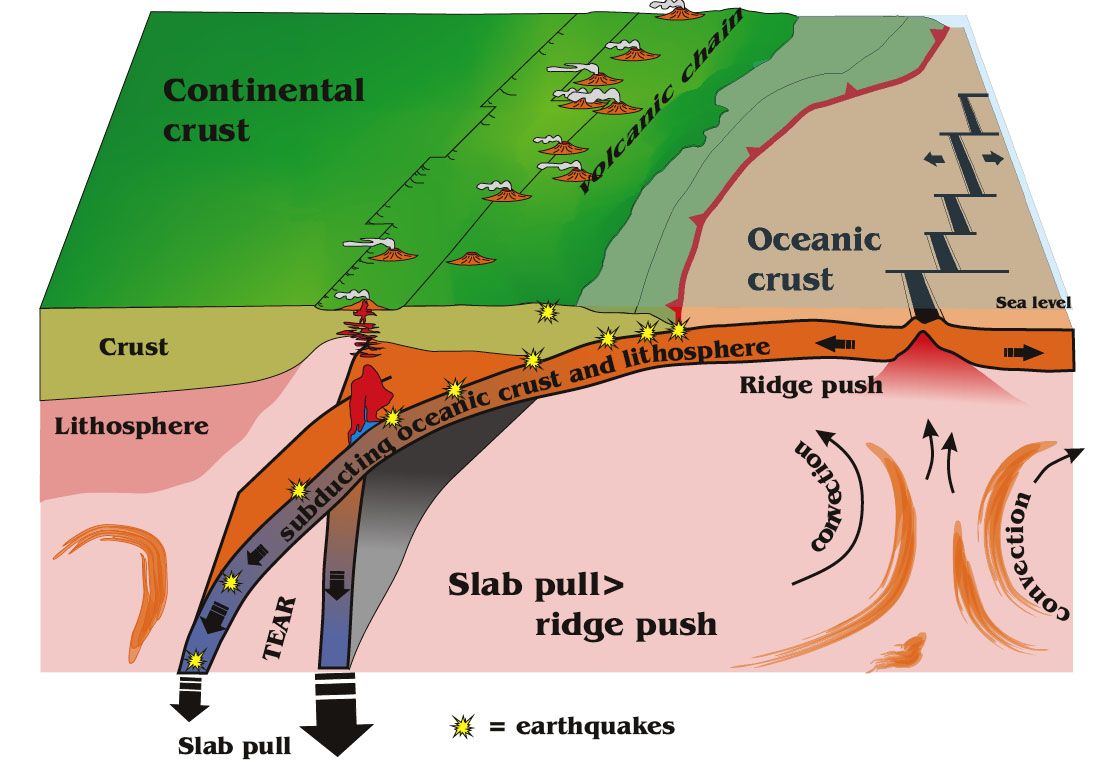

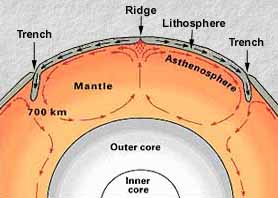

Before the scientific community accepted Wegener’s theories, he was the first to suggest the idea of convective motions in the mantle that would drag the overlying lithosphere portion (below). Holmes’ hypothesis is much remarkable, but still the forces involved in convective motions are too weak to displace a plate.

Convective cells in the mantle – they are more likely to occur only in the upper mantle

Actually, today we see lithosphere as an integral part of the convective cell, the outermost cold portion of the cell, not just a transported slab. At the spot where the hot expanding material rises, melted material is ejected at the surface (continental and ocean rift volcanism) creating new lithosphere. Ocean floors spread from the rift, lifted up by the raising hot material from the asthenosphere. Continental rifts are the place for upcoming formation of new oceans. In this way seafloor spreading separates the continents (as proposed by Wegener for South America and Africa). But if new lithospheric material is being formed, where does the excess material end up?

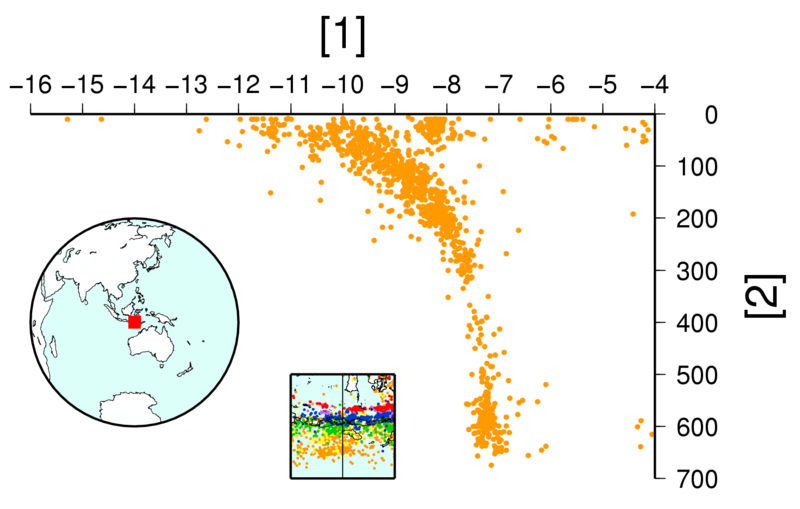

Back to the hypsometric curve, we still have to explain the existence of the few elevation minimums – the ocean tranches. Seismology will come to help. In 1935, the Japanese seismologist Kiyoo Wadati (1902 – 1995), who inspired Charles Richter to create his earthquake magnitude scale, observed how at ocean trenches deep earthquakes extended along a tilted plane up to island arcs like Japan.

In 1949, the American seismologist Hugo Benioff (1899 – 1968), professor at the California Institute of Technology, noticed how earthquake hypocenters recorded along a 50 km belt off the North American Pacific coast were progressively deeper: those with hypocenters down to 300 km of depth were aligned along a 33° trend, while the deeper ones aligned along a 60° trend.

Those dipping seismic hypocenter alignment trends would represent lithosphere slabs dipping into the mantle, causing the deepening seismicity trends. They took the name of Benioff-Wadati zones (below), the most plausible places on Earth where to suppose the excess ocean lithosphere is being consumed (if we rule out the Earth is inflating!). At ocean trenches the ocean lithosphere is subducting, immersing into the asthenosphere.

The bending slab causes the formation of oceanic trenches. Island arcs form from melted material from the descending slab’s partial fusion, as it dips deeper into the mantle. Over the subduction slab is a wedge of asthenospheric material. These are convergent plate boundaries. There we find mountain belts and ocean trenches, the only possible zones where the cold portions of convective cells may descend. The slabs own “weight” would actually trigger the convective motions, as the slab dives into the upper mantle exerting a “pull” on the entire plate, while the expanding ridge “pushes” the plate away.

The Canadian geophysicist John Tuzo Wilson (1908-1993), professor at the University of Toronto, helped completing the picture. By the end of the 30s, Wilson met Hess in Princeton, where he was working at his doctorate program. Hess’ ideas fascinated him deeply. Wilson contributed to the development of the Plate Tectonics theory by confirming Diez’s studies on the Hawaiian hot spot.

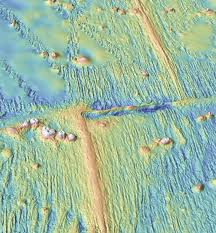

But Tuzo Wilson is renown for having described a third type of plate margin, which connects ocean rifts to ocean tranches: the transform margin. Ocean ridges appear displaced by long fracture zones almost perpendicular the the rift axis.

Ocean floor topography where an ocean ridge is displaced by a fault Wilson will call transform fault

Wilson suggested they were a particular kind of strike-slip faults, faults with horizontal displacement. Their peculiarity, apart from being a plate margin, is they are seismically active only within the portion between the two sectors of rift they dislocate. This because it is the only portion along the transform faults where the lithosphere is moving in opposite directions.

Actually, the real transform fault is just the portion between the two rift segments. Outside it is just a fracture zone, no relative motions. Tuzo Wilson also gave the name to the Wilson Cycle, which describes how the Earth’s continent are continuously aggregating and separating because of tectonic motions.